During Christmas 1891, Dreiser, age twenty-one and miserable as a bill collector in Chicago, decided to find a job as a reporter: "I conceived of newspapers as wonderlands in which all concerned were prosperous and happy. . . I was also determined to shake off the garments of the commonplace in which I seemed swathed and step forth into the public arena, where I could be seen and understood for what I was—a writer." He at last found a slot at the Chicago Daily Globe, helping cover the 1892 Democratic National Convention.

This, in turn, led to jobs with newspapers in St. Louis, Toledo, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh—a scraping, unremunerative, eight-year journey through bustling railroad towns, with New York and Pulitzer's World the final terminal. He started as a reporter, but found greater success as a feature writer, where he was better able to bend fact toward fiction. He specialized in lowlife stories, the research for which was a working education in the brutalities of life: "The police courts, the jails, the houses of ill repute, trade failures and trickery—it was all a grand magnificent spectacle:" a pageant of human weakness, wickedness, and survival through cunning and courage. "Everywhere I looked I found a terrifying desire for lust or pleasure or wealth, accompanied by a heartlessness which was freezing to the soul, or a dogged resignation to deprivation and misery." He covered lynchings, streetcar strikes, robberies and murders—all of it testing his abilities as an observer and awakening the novelist within. It was the school that would prepare him for Sister Carrie (1900), Jennie Gerhardt (1911), and An American Tragedy (1925).

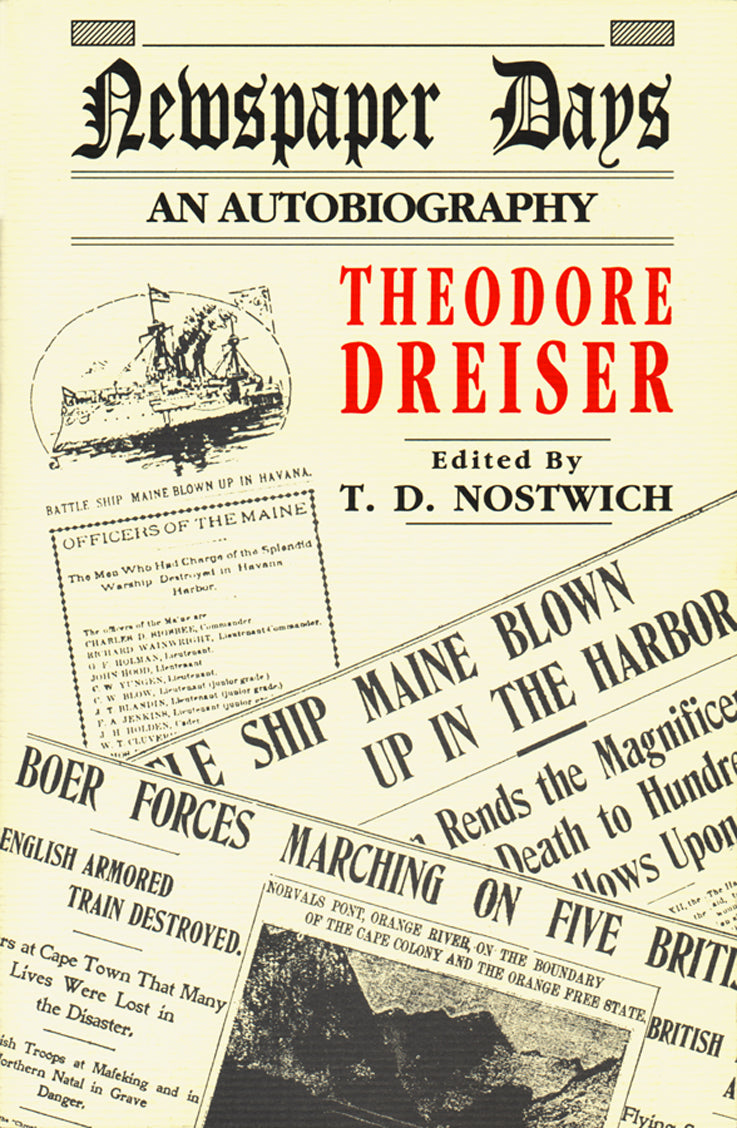

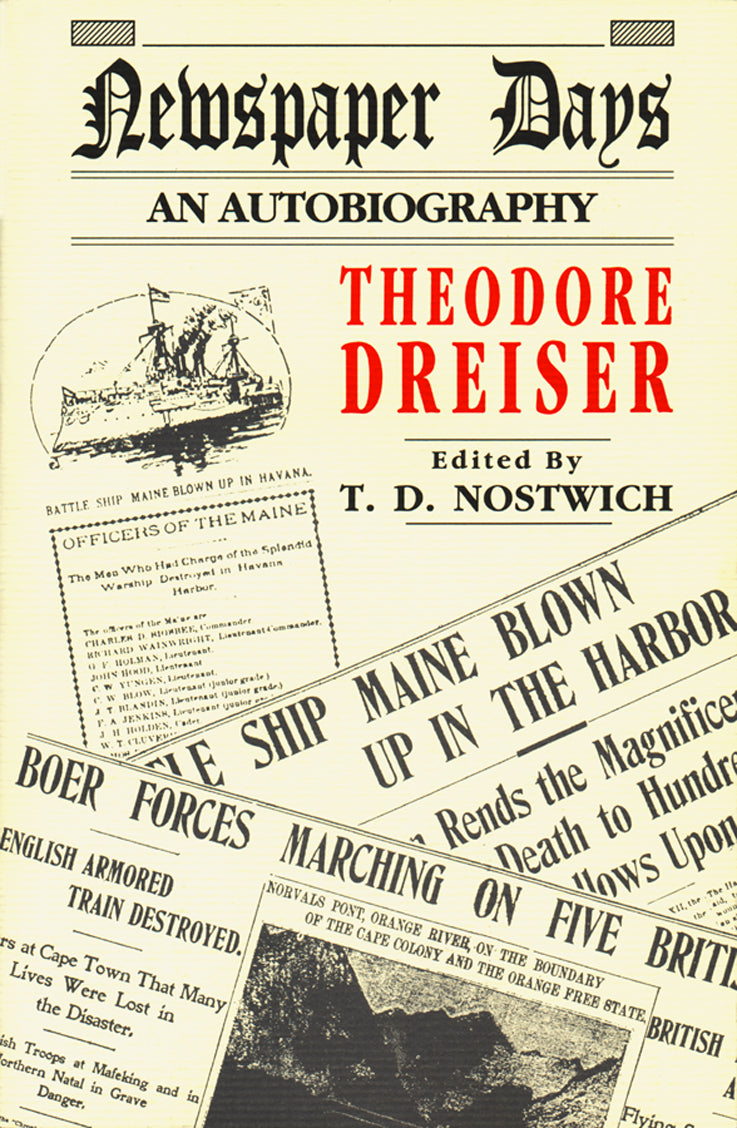

First published in 1922 in what the editor calls an "expurgated abridgment," Newspaper Days is here published in an edition based on Dreiser's original typescript.